Have you ever been in a Yoga class and been given a subtle cue by the instructor that completely changes the way the body feels in an asana (posture)? It’s not uncommon for Hatha Yoga practitioners to feel that they’ve mastered a pose by achieving its outward form. But to deepen and refine one’s practice, it’s ideal to master the subtle actions of a pose as well. Steven Weiss, Yoga therapist and chiropractor with years of experience in alignment, anatomy, and preventing injuries, explains the importance of form and action in a Hatha Yoga practice.

Form Versus Action: Why It Matters in Our Yoga Practice

Consider the following: When driving a car, we mostly think about the ride and rarely about the mechanics under the hood. When listening to a masterful musician, we are absorbed by the beautiful harmonies and tones and often oblivious to the hours of practicing scales and precise fingering. We can watch for hours how a professional dancer moves with amazing grace and refinement without calling attention to their years of tireless practice. The Olympic gymnast displays the ultimate in body control, feats possible only through dedication to details that go beyond our imagination. A golfer is elated when instructed to slightly align his shoulders or move his thumb a half-inch, adding twenty yards to his shot. Yoga practice requires similar discipline. Grace and refinement in our postures requires specific attention to detail. And, that detail is alignment.

The Importance of Alignment

Although some Yoga practitioners hold to the false mythology that alignment makes Yoga constricting and confining, perhaps void of spirituality, most skillful artists will affirm that there is greater spirituality in effective, efficient performance than failing or being unwilling to engage precision in their craft. An airplane is off-course 90% of the time and requires constant, subtle navigation—so does the human body. Easily, we’re in poor posture, we move incorrectly, or we exploit our flexibility. Precise alignment brings us back on course. It almost assures our Yoga practice to advance while being safe and not causing injuries.

Form Versus Action, Appearance Versus Anatomy

There are many aspects of alignment to consider. In this article, we’ll look at the common confusion between form and action. Every Yoga posture has two aspects: an outer form and inner action. The form expresses the outer appearance of a pose. The action engaged in a pose follows the anatomical design of the body. Interestingly, form and action are often significantly different and their engagement seemingly counter-intuitive.

How Specific Actions Affect our Flexibility and Stability

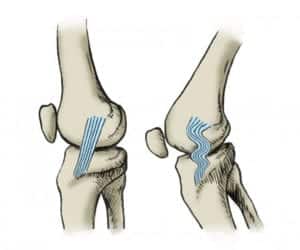

This is all well and good, but we’ll need to know how to access these critical ligament functions. Fortunately, certain directions of joint movement allow ligaments to be either loose or taut:

- Flexion, internal rotation, and adduction loosen ligaments for flexibility

- Extension, external rotation, and abduction tighten ligaments for stability

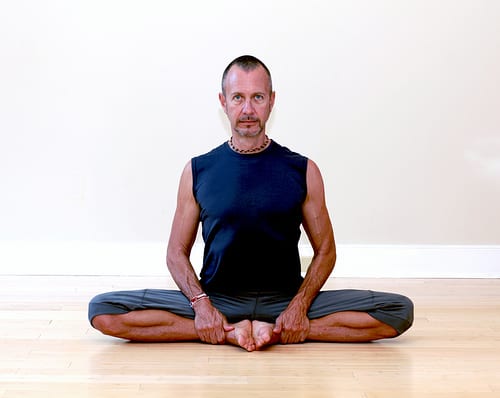

Is this a strange concept, or is it confusing? Take for example, Baddha Konasana, the Cobbler’s Pose.

The form of the pose opens the hips in the directions of external rotation and abduction—two directions that tighten ligaments and restrict joint flexibility. Forcing the hips to directly externally rotate and abduct can overstretch and damage the hips and its ligaments. Instead, the actions in the pose are to draw the thighs inward, deepen flexion (drawing the femur heads back), and internally rotate the upper inner thighs. These actions loosen the ligaments and allow the pose to safely go deeper and farther. Importantly, often the inner action of a pose is subtle and almost energetic in its engagement.

This article was originally published online at Do You Yoga.com.