Swami Satchidananda taught that freedom is a state of mind, no matter your outside circumstances. That teaching may carry even deeper meaning for students of prison Yoga classes. Inspired by the example and teachings of Sri Swami Satchidananda and other teachers, many Yoga instructors today are feeling called to share the practice of Yoga with men and women in prison. There are people in the prison system wishing for a better life and for spiritual direction, and many have been benefited and rehabilitated by this service. We sat down with a local teacher of prison Yoga to hear him share his wisdom and stories.

An Interview with Atman Fioretti of Satchidananda Ashram Prison Project

Rev. Kumari De Sachy’s book, Bound to Be Free.

I first heard of Prison Yoga through my brother, who’s a yogi in the tradition of Siddha Yoga. The Siddha Yoga tradition has a very active Prison Project. My brother is an amazing soul and he got to know a Protestant chaplain working in a prison many years ago in Cincinnati. He already had some experience in counseling prisoners, so as he got deeper into Siddha Yoga he began teaching Siddha Yoga meditation in prisons. He always told me how rewarding it was. When I retired and got my certification for Level I and Level II, the thought that someday I could teach in prisons was always in the back of my mind. The first person I contacted about Prison Yoga was Kumari De Sachy, who wrote the wonderful book, Bound to Be Free. At that point, she was no longer actively involved in the Satchidananda Ashram Prison Project. She sent me to Lakshmi Barsel, who in my estimation is a saint. She does so much and she works so hard with prisoners all around the country. Lakshmi corresponds with prisoners in different institutions; she writes the inmates letters, sends them books, and sometimes goes to visit them.

When I inquired about volunteering, she said, “Well, I’m in touch with the chaplain at a women’s prison and they want to start a volunteer Yoga program for inmates.” So that’s where I began volunteering. Initially there were three of us volunteering, but very quickly the other two teachers dropped out for one reason or another. This kind of seva (selfless service) requires a certain mindset and a certain experience in your life. One teacher just wasn’t up to the challenge. The other teacher eventually got a full-time job and didn’t have the time to volunteer. Very quickly it fell on me, and I would go to the prison once a week to teach these women. The program was voluntary for the inmates, so every six months those who were interested and able (because they hadn’t committed any infractions) would sign up for the class out of their own personal interest. The class would start at first with about 30 women, but, as they learned what the class was like, the number would dwindle a bit. Eventually I would end up with a core group of about a dozen women.

It was an amazing experience. Three of my best and most consistent students there had committed murder. It’s very difficult sometimes to reconcile because you get to know them as Yoga students, not as criminals. I volunteered for about two years with that institution.

Then, there was a break. Naturally, there’s always bureaucracy to navigate, but prison bureaucracy can be particularly cumbersome. The chaplains kept changing at the prison. The first chaplain I worked with really supported the program wholeheartedly. To have that kind of support from the chaplain was really instrumental in having the program continue. I went away to Florida for a month and when I came back I was told by administration that they were doing a reorganization. Eventually my participation at the women’s prison ended. My life went on, I did some travelling, I spent a long winter in Florida, and then I came back home and I was getting restless and anxious. I wanted to see, after having a couple years of experience volunteering in a women’s prison, what it would be like to volunteer in a men’s prison. It’s such a learning experience to teach in prisons, and I just wanted to broaden that experience.

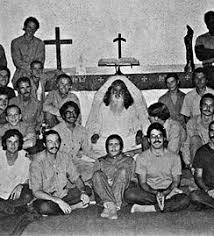

Sri Gurudev poses with the Yoga class of inmates at Soledad Prison, USA, early 1970s.

The timing was again, perfect. I came back from my travels and Lakshmi told me that the local men’s prison was in search of a Yoga teacher. Again, it was the grace of the Guru—it just fell into my lap. Teaching at the men’s prison is different than my past experience in a couple of ways. First, there’s a difference in relating to the men compared to relating to the women. Suffice it to say, it’s different. The other difference is that my Yoga class at the men’s prison is being offered as a part of a therapeutic program.

This program was organized by the prison’s psychologist, who is also a great soul. His name is Dr. Lightbody. He’s very bright and very dedicated to the goal of improving life for the inmates. The inmates that are accepted into this program live in a cell block called a pod, which accommodates 64 inmates. They all live together and are part of a holistic program for dealing with stress, anger, and mental health issues. They have access to group therapy, individual therapy, and art therapy. The warden has designated an area for them outside where, in the spring, they can have their own garden. They engage in journaling and they practice Yoga.

At the men’s prison, the inmates have to participate in the program whereas in the women’s program it was voluntary. There are 64 guys, so I have two classes of 32 students. Not all 32 are present for every class due to doctor’s appointments, work assignments, and classes, so every Monday and every Friday there are roughly 18-30 men in my class. It’s a big group.

When people ask me about Prison Yoga, my answer is that it’s always challenging, but it’s always rewarding—no matter what happens. I have talked to people who have expressed interest in teaching prison Yoga, and again I’ve realized that you have to have a certain mindset and a certain set of experiences to be able to work within the prison. You have to have a firmness about you; you can’t be afraid. The inmates know it right away if you’re not at ease with them. You have to have their respect. I’ve had, in my youth, brushes with the law. In relating to the inmates, it doesn’t hurt that I’ve been exposed to the system personally. When I got involved in Yoga, it was a major change in direction in my life; it helped me gain control of anger issues. I feel like I can relate to these guys on a firsthand basis.

The doctor who has organized the therapeutic program is so amazing. He recently held a graduation for the inmates who had successfully completed six months of the therapeutic program. I went to the graduation just last week. The gym was all set up and there were all my guys! They held a great program—they even had an inmate band. Every inmate that finished the 6 months received some kind of recognition in writing. You could see them smiling, glowing, and just enjoying it. I was overwhelmed. I attended not knowing that the graduation was specifically for our group. It was amazing.

This program description (below) from the graduation ceremony will give you an understanding of the program’s purpose. Because of the failure—not completely, but generally—of the mental health system in this country, prisons have become de facto mental institutions. The statistics that I’ve heard in the last few months are that anywhere from 25-35% of all inmates in all prisons in this country have fairly serious mental health issues. Initially I didn’t understand the purpose of the therapeutic program or why the inmates a part of it.

Program Description: The Shared Allied Management Unit is a residential pod intended to provide a safe environment for the delivery of intensive services to individuals that typically require a high level of services from security, mental health, and/or medical department which will include: Individuals with a mental health diagnosis that present management difficulties in GP or frequently cycle in and out of Special Housing and/or the licensed mental health units. Individuals with a medical condition requiring frequent nursing attention but not requiring admission to the infirmary. Individuals vulnerable to predation, bullying, or manipulation due to characteristics such as an intellectual challenge, age, or size.

That’s how I learned that the program specifically targets these inmates and aims at improving their life and situation. Teaching such a population sometimes presents certain challenges in class, and I have to learn how to accommodate them. For instance, a student has told me that he needs more space around him in class because he suffers from paranoia.

Sometimes there are also incidents in class and I may have to confront the inmates and let them know that their behavior isn’t acceptable. I may have to stand up to these convicted felons and tell them no. Even in the women’s prison it was the same way. If it comes to a point where someone is being disruptive and is disturbing someone else who wants to be there, you have to be firm. Master Sivananda always said: “Adjust, adapt, accommodate.”

In the program, all 64 guys are focusing on improvement. They have group leaders and a structure. It’s a privilege for them to be a part of the program. If they don’t want to participate in the program, they’re out. There is a long waiting list, so the doctor doesn’t fool with those who don’t want to participate. Teaching there is so gratifying because I know it’s having a positive effect on them and I really feel that I am part of their community.

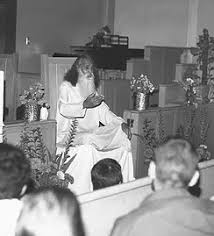

Sri Gurudev gives a talk on Yoga to inmates at Tracy Prison, USA, early 1970s.

There are definitely some other ways I have to ‘adapt, adjust, accommodate’ when teaching in prisons. For example, I don’t use Sanskrit. Instead of saying pranayama, we call it breath control. When I was working with the chaplain [at the women’s prison], it was a regular Level I class. With the guys, it’s part of a therapeutic program and Dr. Lightbody asked that I stress pranayama, deep relaxation, and meditation as these practices have a direct impact on stress. I’m always very clear that Yoga is a philosophy and I emphasize that the practices help you deal with stress. I don’t want a someone to think that Yoga is a religion. But some of the inmates are exploring on their own and going to a Siddha Yoga meditation class taught by an inmate. When I know that, I can use a different language with those students.

When I had a student who wanted to learn more about mudras and pranayama, I got him a copy of Swami Satchidananda’s book, Breath of Life. I was happy that I could provide him with some resources to learn more. I’m excited that he’s so curious.

I looked around at the students in my class last week—they’re as good of a class as any I’ve ever taught! They were all engaged in the practice and focused, but it took 6 months to get to that point. There’s no doubt that I’ve seen their growth. They also had to adjust, adapt, and accommodate! Gurudev always said that you could make prison into an ashram, and I tell them that.

For anyone who is interested in teaching prison Yoga, my first suggestion is to read Kumari’s book, Bound to be Free. It’s also very helpful to speak to someone who has done it. Teaching prison Yoga is a service that is so needed.

I’m volunteering in a state prison, but you could also teach in federal prisons. I’ve talked to some Yoga teachers who are interested in volunteering in jails. Jails differ from prisons because many people there are serving shorter sentences—there is a lot of turnover. The prison where I’m currently serving is ideal, I think, because the doctor has the support of the warden, and the warden has the support of the Virginia Department of Corrections. There are other places and different experiences, however. Perhaps not every institution is so progressive.

A good way to start volunteering is to contact the chaplain of the institution. The chaplain might be involved in a similar therapeutic program such as the one at the men’s prison. In the south, you might run into people that are more conservative and unfamiliar with Yoga. The first chaplain I worked with was a Baptist minister, but she was supportive of the program because it works! Yoga is more widely accepted now than it used to be.

I have such fun teaching in prisons, and it’s a great conversation starter! I have had a very blessed existence. If I can’t give just a little back, then God will take me because I’ll be worthless! I’m grateful to serve in this way.

Want to learn more about Prison Yoga?

Click here to read more about Satchidananda Ashram Prison Project. Feel inspired to make a donation? Visit our Donations page and select “Yogaville Prison Project.”