“Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people.”

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations, 1948

I imagine that for most people talking about Yoga and human rights in the same sentence may seem strange. But this connection became clear in my mind when I had the privilege of attending a special event at the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva in 2015. The event was the celebration of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, December 3, a holiday established by the UN. That year, I was invited to teach Accessible Yoga as part of a variety of offerings focusing on the positive steps that people with disabilities can take to achieve full equality and human rights.

Most of the other presenters were leaders of disability rights groups from around the world. They spoke about how people with disabilities make up the largest minority group in the world: well over 1 billion people! And they discussed the basic human rights that they are seeking for people with disabilities. In 2006, the UN’s Human Rights Commission set the gold standard for these human rights in their Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. They declared:

“The purpose of the present Convention is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.”

Article 1, United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

I was struck by the correlation between basic human rights and the fundamental teachings of Yoga philosophy. According to the Yoga tradition, each person has a spiritual essence, which is called the atman or purusha. The work of Yoga—the poses, breathing practices, ethical living, and meditation —are all about opening the pathways to the experience of that essence. I’ve always loved the fact that Yoga begins with this positive assumption. The idea is that every single one of us has an atman, and that there is no differentiation made between the atman of any two people, regardless of their ability or background. Yoga begins with equality, as we are all equal in spirit. And because we are all equal in spirit, Yoga is equally powerful in helping anyone, of any background or ability, to find the inner peace that we all crave.

Of course, embracing diversity is an essential part of human rights, and the disability community is extremely diverse. There is currently a shift in the disability community towards disability pride, towards embracing difference. As a gay man, pride has a special meaning to me. I grew up thinking that being gay was a deficit, and learning to be proud of my differences has been a great source of my healing. Now, I am not only proud of being gay, but I see how being different makes me stronger.

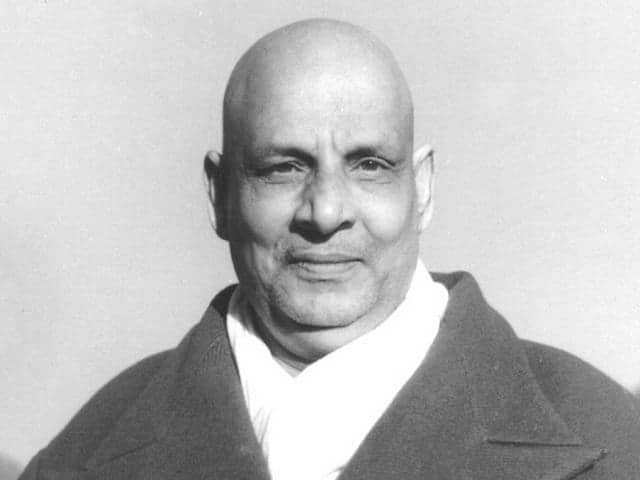

Swami Sivananda, a famous Yoga master, used to say that spiritual life was about seeing the “unity in diversity.” This means being able to see that we are all connected, and to simultaneously embrace our differences. Yoga and human rights both stem from this dual vision—the ability to hold both equality and diversity simultaneously.

Master Sivananda

It’s really a paradox: we are all the same and yet all unique. This perspective is challenging in a modern world where some people are empowered and some are not, a world that is filled with division and the separation of groups based on race, class, gender identity, political affiliation, etc. Our job as Yoga practitioners, and human rights advocates, is embrace those differences and at the same time to see the same essence in everyone we meet.

According to the Bhagavad Gita, one of the most essential texts of Yoga, as we become more in tune with ourselves, we begin to experience that underlying connection with others. Lord Krishna, who is teaching Arjuna how to be a yogi, explains:

“As your mind becomes harmonized through Yoga practices, you begin to see the Atman in all being and all beings in your Self; you see the same Self everywhere and in everything. Those who see me wherever they look and recognize everything as my manifestation, never again feel separate from me, nor I from them. Whoever becomes established in the all-pervading oneness and worships me abiding in all beings – however he may be living, that yogi lives in me. The yogi who perceives the essential oneness everywhere naturally feels the pleasure or pain of others as his or her own.”

(6.29-32 translation by Swami Satchidananda).

Just seeing through the diversity of nature to experience the oneness of creation isn’t enough. Krishna is teaching us that once we go down that path, we will literally feel the pleasure and pain of others as our own. That’s the ultimate level of awareness – true connection. And that is the first step on the path to equality and human rights. If we feel intimately connected to others, then we automatically take care of them. But this can only happen if we understand our personal privilege and the perspective we are coming from, otherwise that concept of oneness can be used to avoid the harsh reality of human rights abuse and leave us complacent. This is called spiritual bypassing.

“Spiritual bypassing perpetuates the idea that the belief “we are one” is enough to create a reality where we are treated equally and as one. It is not. Spiritual bypassing permits the status quo to stay in place and teaches people that if you believe in something and have a good intent that is enough. It is not.”

Michelle Cassandra Johnson

Those of us in positions of power and authority can use our Yoga practice to reveal hidden truths in our own behavior and attitude—things we may not want to see in ourselves. The practice of svadhyaya, or reflection, is an essential part of Yoga. In svadhyaya we attempt to witness the workings of our own mind, to see our ego and its prejudices. In the self-reflection that our practice brings, we can consider this question: Are my efforts reinforcing the status quo or is my practice inspiring me to actively work on achieving human rights for all?

Regarding ableism specifically, Yoga teachers can reflect on whether unknowingly they may be teaching Yoga in a discriminatory way. For example, am I teaching in a wheelchair-accessible space? Am I teaching in a way that values physical ability as superior or advanced? Am I giving all students the same respect, attention, and kindness regardless of ability? Are my offerings advancing equality in the Yoga community? What can I do to cultivate svadhaya in myself, in my students, and in my peers?

We can also examine our language: Am I reinforcing stereotypes that I am also the victim of? For example, do I hide my own physical challenges out of an effort to seem like the perfect yogi, rather than honestly share with students about where I am at? Can I examine the culture of the Yoga studios I teach or visit to see if they are in line with my own beliefs? Do the social media accounts I follow make me feel better about myself or reinforce insecurity and self-doubt?

For those of us who are oppressed or lacking in human rights, we can use our Yoga practice as a source of power and healing. That means seeking out supportive Yoga communities that don’t make us feel less than but rather help to lift us up. In this way, we can use Yoga as self-care and as a source of empowerment. According to Audre Lorde:

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

Audre Lorde

This paradox of unity and diversity is at the heart of Yoga and at the heart of human rights. With practice, self-awareness, and action, we can deepen our experience of Yoga, connecting with our true self and simultaneously begin to honestly and openly address human rights and discrimination of all kinds.

This post was originally published on the Yoga for Healthy Aging blog, where it was edited by Nina Zolotow. It was also republished on the Accessible Yoga blog.